Imagine a time when the known universe felt complete, yet a persistent whisper of the unknown beckoned astronomers to look just a little further. This wasn't a story of grand, cosmic theories alone, but one deeply human: driven by intuition, meticulous observation, groundbreaking technology, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. It's the story of Pluto's Origin and Creation History, from a hypothetical "Planet X" to a dynamic dwarf world that continues to challenge our understanding of the solar system.

Pluto’s journey from a blurry photographic speck to a vibrant, geologically active body captured by the New Horizons spacecraft is a testament to scientific curiosity. It’s a narrative punctuated by brilliant minds, painstaking work, surprising discoveries, and even a controversial reclassification that sparked a global debate.

At a Glance: Pluto's Unfolding Story

- Born from Hypothesis: The idea of a ninth planet, "Planet X," was first proposed by Percival Lowell in the early 20th century to explain anomalies in outer planet orbits.

- A Fortuitous Discovery: Young, self-taught astronomer Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto in 1930, after a painstaking search at Lowell Observatory.

- Unveiling Its Family: Pluto's largest moon, Charon, was discovered in 1978, revealing a binary-like system.

- A Breath of Air: Evidence of a thin atmosphere was detected in 1988, adding to Pluto's mysterious character.

- The Close-Up: NASA's New Horizons mission in 2015 provided humanity's first detailed look, transforming Pluto from a distant point of light into a complex, active world.

- Identity Shift: In 2006, the International Astronomical Union controversially reclassified Pluto as a "dwarf planet," sparking ongoing debate among scientists and the public alike.

The Whispers of Planet X: Lowell's Grand Obsession

The stage for Pluto's eventual discovery was set long before anyone had seen it. At the turn of the 20th century, American astronomer Percival Lowell, famous for his controversial claims about "canals" on Mars, became obsessed with a more distant enigma. He hypothesized the existence of a massive, unseen planet beyond Neptune, which he dubbed "Planet X."

Lowell first publicly shared this idea in December 1902 at MIT, elaborating on it in his 1903 book, "The Solar System." Initially, his belief stemmed from perceived links between meteor streams, like the Perseids and Lyrids, and a planet he estimated to be about 45 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. However, his focus soon shifted to subtle, unexplained irregularities in Neptune’s orbit, which he believed could only be caused by the gravitational tug of an undiscovered body.

Driven by this conviction, Lowell initiated "The Invariable Plane Search" in 1905 at his observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. It was a Herculean task, blending telescopic photography with complex mathematical calculations. He employed a dedicated team, including "human computers"—often women, led by Elizabeth Williams—who performed the intricate computations needed to predict where Planet X might reside. Initially using a 24-inch Clark Refractor, Lowell later added a 5-inch Brashear telescope to his arsenal.

By 1910, fueled by the competitive spirit ignited by rival astronomer William Pickering, Lowell intensified his efforts. He upgraded his equipment, employing improved telescopes, including a nine-inch instrument borrowed from Sproul Observatory, and even a Millionaire calculating machine to aid in the exhaustive mathematical work. Ironically, photographic plates captured images of Pluto as early as 1915, but they were too faint and indistinct to be identified as a planet at the time. Lowell published his definitive mathematical predictions in "Memoir on a Trans-Neptunian Planet" in 1915, yet he passed away in 1916 without ever seeing his elusive Planet X. The search, for a time, came to a halt.

A New Chapter: Tombaugh and the Blink Comparator

The quest for Planet X might have languished indefinitely had it not been for the determination of Lowell's nephew and trustee of Lowell Observatory, Roger Lowell Putnam. In 1927, he successfully revived the search, securing a crucial donation of $10,000 from Percival Lowell's brother, Abbott Lawrence Lowell (then president of Harvard University). This funding allowed the observatory to acquire a new 13-inch astrograph—a specialized photographic telescope—which arrived in February 1929.

To operate this cutting-edge equipment, observatory director V. M. Slipher hired a remarkable young man named Clyde Tombaugh. A 23-year-old self-taught astronomer from Kansas, Tombaugh brought an unparalleled dedication to the task. He took his first photographic plate on April 6, 1929, systematically examining the precise sky areas Lowell had indicated in his 1915 memoir.

Tombaugh's method was arduous and painstaking. He spent an estimated 7,000 hours over 14 years at the eyepiece of a blink comparator, a device that allowed him to rapidly switch between two photographic plates of the same region of the sky, taken days or weeks apart. Stationary stars would appear still, but any object that had moved would seem to "blink" or "flicker" between positions. This required immense concentration and keen eyesight.

On February 18, 1930, while meticulously examining plates of the Delta Geminorum region taken on January 23 and 29, Tombaugh spotted it: a faint image that flickered in and out of view. He carefully measured its position, cross-checked backup plates, and confirmed the mysterious object's expected appearance. The excitement was palpable. Tombaugh immediately called his colleague Carl Lampland, then announced to V. M. Slipher, "Dr. Slipher, I think I found your Planet X." The three men, after careful verification, confirmed it was indeed a planet. Although cloudy skies initially delayed immediate photographic confirmation, Tombaugh successfully captured the object again on a subsequent night.

The discovery was officially announced on March 13, 1930. This date was strategically chosen, not only marking Percival Lowell’s 75th birthday but also the anniversary of Uranus’s discovery in 1781. V.M. Slipher sent a telegram to Harvard College Observatory the previous evening, leading to Harvard College Observatory Announcement Card 108. The new planet was named Pluto, after the Roman god of the underworld. Its symbol, a combination of "P" and "L," was also a subtle yet fitting tribute to Percival Lowell. You can learn more about its cultural impact, for instance, with the beloved Disney character, Pluto.

Pluto's Growing Family: Charon and Beyond

For decades after its discovery, Pluto remained an enigmatic point of light, its true nature hidden by vast distances. Then, in 1978, Jim Christy of the U.S. Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station (NOFS) made another groundbreaking discovery: Pluto wasn't alone.

While examining photographic plates taken by Anthony Hewitt at NOFS in April and May 1978, Christy noticed something peculiar. Pluto appeared slightly elongated, almost asymmetrical, and this "bulge" seemed to migrate around it over successive images. He concluded that this wasn't an anomaly of the telescope but rather evidence of a moon orbiting Pluto. By carefully tracking its movement, Christy determined its orbital period to be 6.39 days.

Christy named this new companion Charon, combining a nickname for his wife, Charlene ("Char-on"), with the mythological ferryman of the River Styx, who transported souls to the underworld—the domain of Pluto. This clever naming scheme not only honored his family but also perfectly fit the long-standing tradition of scientific naming rules, forging an indelible link between the two celestial bodies.

A Glimmer of Atmosphere: Peeking Behind the Veil

As technology advanced, so did our ability to probe Pluto's secrets. A decade after Charon's discovery, in 1988, scientists detected Pluto's atmosphere. This wasn't a direct observation, but an ingenious deduction made possible by a stellar occultation—when Pluto passed directly in front of a distant star, temporarily blocking its light.

Scientists, including Elliot's MIT team (with Ted Dunham) and ground-based observers (like Bob Millis and Ralph Nye), utilized the Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO) and other telescopes for this crucial event on June 9, 1988. If Pluto had no atmosphere, the star's light would have abruptly winked out and then reappeared. Instead, observers witnessed a gradual dimming and brightening, a tell-tale sign that the star's light was being refracted and absorbed by a thin veil of gas around Pluto.

This thin atmosphere was later found to consist primarily of nitrogen, along with methane and carbon monoxide. This groundbreaking discovery added another layer of complexity to Pluto, making it much more than just a frozen rock. In the mid-1990s, Marc Buie further utilized the Hubble Space Telescope to create the first albedo maps of Pluto, hinting at varied surface features long before we could see them clearly.

New Horizons: The Close-Up Revelation

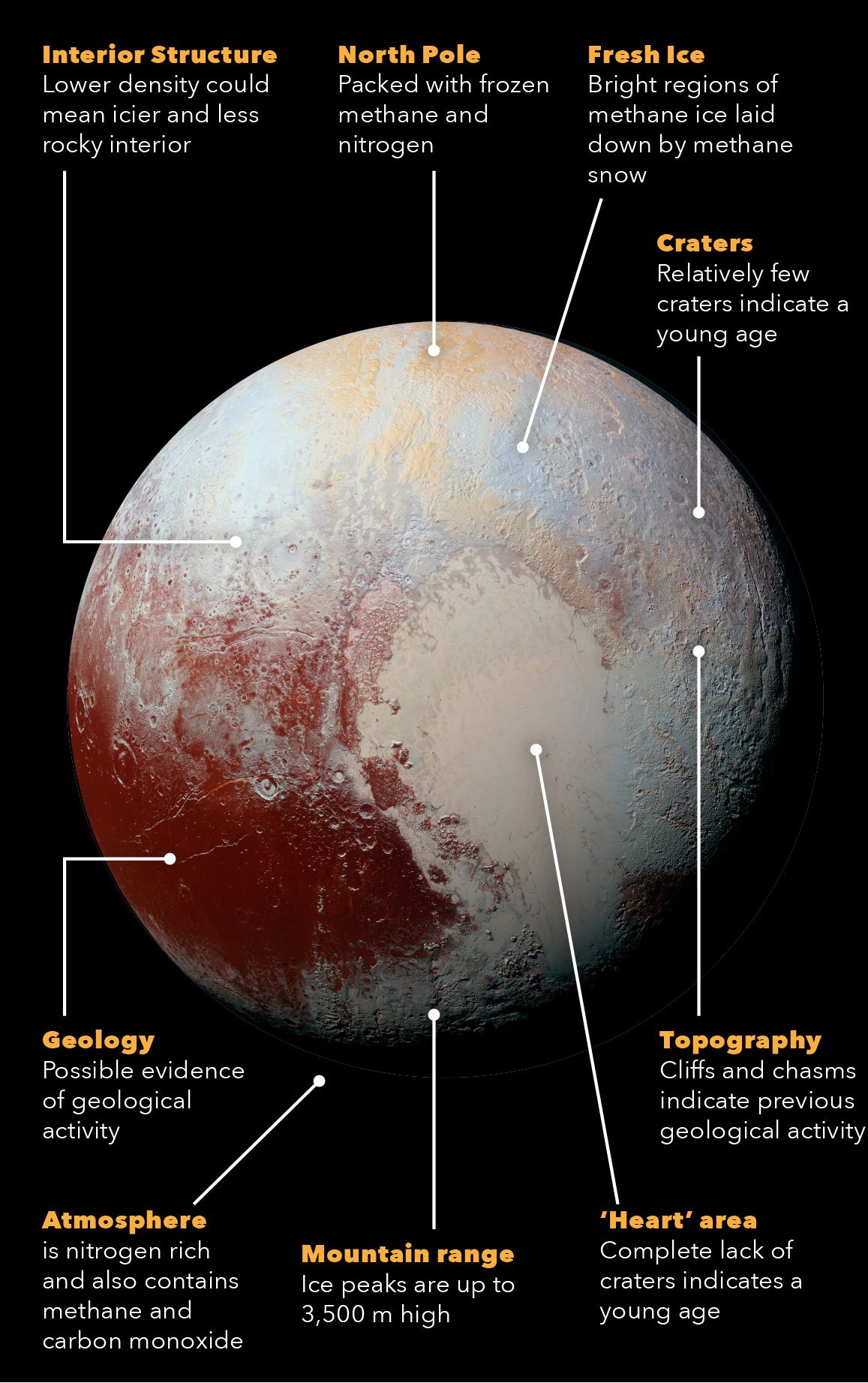

For decades, Pluto remained a fuzzy, distant smudge, its secrets shrouded by billions of miles. Then came NASA's New Horizons spacecraft. Launched in 2006, it embarked on a nearly ten-year journey to deliver humanity's first up-close look at this mysterious world. On July 14, 2015, New Horizons successfully completed its historic flyby, forever transforming our understanding of Pluto. Will Grundy, who headed the mission's surface composition team, was among many scientists with deep ties to Lowell Observatory who were involved in this monumental mission, bridging the past and present of Pluto exploration.

The data transmission from New Horizons was a testament to the challenges of deep-space exploration. With a mere 24 watts of power and a 7-foot antenna, the data trickled back to Earth at an agonizingly slow rate of about 2 kilobits per second. It took approximately 1.5 years for all the priceless information to arrive, slowly painting a vibrant picture of a world far more active and complex than anyone had imagined.

According to Principal Investigator Alan Stern, New Horizons delivered a treasure trove of unexpected findings:

- Surprising Complexity: Both Pluto and its family of satellites exhibited an unexpected degree of intricacy.

- Geological Youth: The mission revealed astounding evidence of current geological activity and remarkably young surfaces on Pluto, suggesting ongoing processes.

- Atmospheric Mysteries: Pluto's atmosphere boasts complex hazes, and its atmospheric escape rate was found to be lower than initially predicted.

- Charon's Tectonic Past: Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, displayed an enormous equatorial extensional tectonic belt, strongly hinting at the former presence of an internal water-ice ocean.

- Pluto's Hidden Ocean: Evidence emerged suggesting Pluto itself could harbor an internal water-ice ocean even today.

- A Unified Origin: All of Pluto's age-dated moons share the same ancient age, supporting the theory that they formed from a single, massive collision.

- Charon's Red Cap: Charon's distinctive dark, red polar cap is possibly composed of Pluto's escaped atmospheric gases, captured and processed on its moon.

- Sputnik Planum: Pluto boasts a spectacular 1,000-kilometer-wide, heart-shaped nitrogen glacier, Sputnik Planum, which is the largest known glacier in the solar system.

- Past Liquid Volatiles: Evidence of vast changes in atmospheric pressure and possibly past liquid volatiles on its surface was found, a phenomenon seen only on Earth, Mars, and Titan elsewhere in the solar system.

- A Quiet Neighborhood: Contrary to some predictions, New Horizons did not discover any additional Pluto satellites beyond those already known before its arrival.

- A Blue Hue: Perhaps one of the most visually stunning discoveries was that Pluto's atmosphere is distinctly blue.

The New Horizons mission didn't just give us data; it gave us a whole new world, pushing the boundaries of what we thought was possible in the outer solar system.

The Dwarf Planet Debate: A Cosmic Identity Crisis

Amidst these spectacular discoveries, Pluto faced a significant, and controversial, reclassification. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) voted to redefine what constitutes a "planet." Under the new criteria, a celestial body must:

- Orbit the Sun.

- Be massive enough for its own gravity to pull it into a nearly round shape.

- Have "cleared the neighborhood" around its orbit.

It was this third criterion that Pluto failed. While it met the first two, its orbit shares space with thousands of other Kuiper Belt objects, meaning it hadn't gravitationally dominated its orbital path. Consequently, the IAU controversially reclassified Pluto as a "dwarf planet."

The reclassification vote itself was criticized for occurring during the waning days of the IAU’s general assembly, when many planet specialists had already left. The definition was also deemed convoluted and nonexclusive by some, particularly the first criterion, which explicitly requires orbiting the Sun, thereby excluding the growing number of exoplanets discovered orbiting other stars.

Despite the IAU's ruling, the debate over Pluto’s planetary status persists fiercely among the public and within the scientific community. For many, Pluto remains the beloved ninth planet, a symbol of our solar system's diversity. This ongoing discussion, regardless of one's stance, symbolizes humanity's enduring drive to explore, question, and continually refine its understanding of the universe. It reminds us that our cosmic definitions are not static but evolve with new knowledge. The question of how we classify celestial bodies is a rich subject, highlighting the evolving definitions of celestial bodies and the dynamic nature of scientific understanding.

The Legacy of a Discovery: The 13-inch Astrograph's Journey

The 13-inch Lawrence Lowell Telescope, the very instrument that Clyde Tombaugh used for Pluto's discovery, played a significant role beyond that initial triumph. It continued its relentless search for other potential planets until 1942, ultimately covering an astonishing 75% of the sky.

After its planetary hunting days, the telescope transitioned to other vital astronomical work, studying asteroids, comets, and the satellites of other planets. From 1970 to 1980, it was moved to Lowell’s Anderson Mesa site and used for a proper motion survey of stars, meticulously tracking their subtle shifts across the celestial sphere.

On August 11, 1993, the telescope returned to its original dome on the main Lowell campus for public display, allowing visitors to connect directly with a piece of astronomical history. After 87 years of near-constant use, the instrument underwent a much-deserved refurbishment between 2016 and 2018, ensuring its legacy continues to inspire future generations of stargazers and scientists alike.

What Pluto Still Teaches Us

Pluto's origin and creation history is more than just a timeline of discoveries; it's a profound narrative about the scientific process itself. From Percival Lowell's initial, flawed, yet ultimately catalytic hypothesis, to Clyde Tombaugh's diligent, lonely search, to the awe-inspiring close-ups from New Horizons, Pluto has consistently pushed the boundaries of our knowledge and imagination.

Whether you consider it the ninth planet or a king among dwarf planets, Pluto’s story teaches us that the universe is far more intricate and surprising than we can ever fully predict. It underscores the importance of persistent curiosity, meticulous observation, and the willingness to challenge our existing classifications as new data emerges.

The journey to understand Pluto isn't over. Its history is still being written with every new analysis of New Horizons data and with every future mission that might one day return to this distant, captivating world. It reminds us that the quest for knowledge is endless, and the cosmos always holds more secrets waiting to be uncovered. So, the next time you look up at the night sky, remember Pluto, and the incredible, human story of its discovery and evolution in our understanding.